When adventurers, athletes, and professionals gear up for the wildest environments on Earth, the question is never just about style or comfort. It’s survival. Whether it’s the subzero chill of polar landscapes, the relentless heat of desert dunes, or the crushing pressure of deep-sea dives, the gear we trust can mean the difference between triumph and catastrophe. But how do you know if your equipment is truly built for extreme conditions—or just a fashionable imitation? This article delves into the science, engineering, and practical testing behind high-performance gear, so you can separate hype from reality.

Understanding Extreme Conditions

Before we examine the gear itself, let’s define “extreme conditions.” This is more than just bad weather or rugged terrain. True extremes push materials and humans beyond typical operational thresholds:

- Temperature extremes: Subzero arctic cold (-50°C/-58°F) or scorching desert heat (50°C/122°F).

- Altitude extremes: High-altitude mountain ranges above 5,000 meters, where oxygen is scarce.

- Pressure extremes: Deep-sea diving or high-speed aerodynamics that challenge structural integrity.

- Moisture extremes: Torrential rain, snow, or immersion in saltwater.

- Mechanical extremes: Abrasion, impact, vibration, and fatigue that can compromise durability.

Understanding these categories is critical. Gear that excels in one extreme may fail in another. For instance, down jackets are excellent for cold but offer no protection against water unless properly treated.

Materials Matter: The Backbone of Extreme Gear

The foundation of extreme-condition gear is the material. Modern adventure equipment leverages advanced materials science to withstand nature’s fury.

Metals and Alloys

- Titanium: Lightweight, corrosion-resistant, strong. Often used in high-end climbing hardware and aerospace applications.

- Stainless Steel: More affordable, corrosion-resistant, excellent for marine gear.

- Aluminum Alloys: Perfect for tent poles, trekking poles, and frames; lightweight with a good strength-to-weight ratio.

Each metal has its limits. Titanium, for instance, is incredibly strong, but it’s expensive and can be tricky to machine. Aluminum is versatile, but in extreme cold, it may become brittle.

Synthetic Fabrics

- Cordura® Nylon: Highly abrasion-resistant, ideal for backpacks and protective clothing.

- Gore-Tex® and eVent®: Waterproof yet breathable membranes for jackets and boots.

- Dyneema® and Spectra®: Ultra-high-molecular-weight polyethylene fibers; used in ropes, slings, and high-strength protective gear.

Synthetic fabrics aren’t just about staying dry—they control moisture, temperature, and even resist UV degradation. A jacket rated “waterproof” without breathability will turn into a sweaty trap within hours.

Insulation Materials

- Down: High warmth-to-weight ratio; loses insulation when wet unless treated.

- Synthetic Fill (Primaloft®, Thinsulate®): Maintains warmth even when wet; often heavier than down.

Choosing insulation is a balance between warmth, weight, and moisture management. Extreme-condition gear often combines materials strategically to maximize performance.

Engineering Design: More Than Just Material

Even the strongest material fails if poorly designed. Engineering determines how gear behaves under stress, temperature, and repetitive use.

Structural Integrity

High-performance gear is engineered to distribute stress evenly. Consider tents: lightweight poles alone aren’t enough—they need shock cords, tensioning systems, and aerodynamic shaping to withstand high winds. Similarly, backpacks use load-bearing frames and tensioned webbing to reduce pressure points and prevent structural failure.

Layering and Modularity

Modern extreme-condition gear often adopts a modular approach. Think about layered clothing systems:

- Base layer: Moisture-wicking, next-to-skin comfort.

- Mid layer: Insulation and temperature regulation.

- Outer layer: Windproof, waterproof, and abrasion-resistant.

This layering principle extends to other gear. Mountaineers often carry modular cooking systems, while divers rely on wetsuits with removable thermal layers.

Ergonomics and Human Factors

Even the most durable gear is useless if it’s uncomfortable. Extreme-condition gear is ergonomically designed to reduce fatigue, improve efficiency, and protect joints and muscles. Advanced backpacks, for example, use adjustable harnesses, load lifters, and ventilated back panels.

Real-World Testing: Proof of Performance

Lab specifications are helpful, but extreme-condition gear earns its reputation in the field.

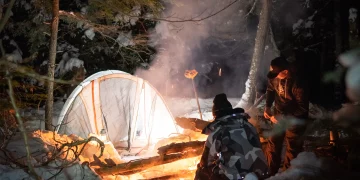

Cold-Weather Testing

- Gear is subjected to freezing temperatures in controlled chambers and on expeditions in polar regions.

- Jackets are tested for insulation efficiency (clo value) and breathability (Moisture Vapor Transmission Rate).

- Boots are evaluated for frostbite prevention, waterproofing, and traction on ice.

A jacket that looks thick may still fail in -30°C winds if the seams aren’t sealed and the insulation compresses under weight.

Heat and Desert Testing

- Clothing and hydration systems face intense heat, sand abrasion, and high UV exposure.

- Materials are checked for reflectivity, airflow, and moisture-wicking.

- Footwear must prevent blisters and maintain grip on shifting sands.

Heat isn’t just uncomfortable—it’s dangerous. Gear that traps heat can accelerate dehydration and heat stroke.

Mechanical and Impact Testing

- Climbing hardware is drop-tested and load-tested beyond expected limits.

- Helmets undergo impact tests simulating rockfall or high-speed falls.

- Backpacks are loaded with weight cycles to simulate repeated use without structural failure.

Extreme mechanical testing ensures gear won’t fail when it’s needed most.

Common Misconceptions About Extreme Gear

Many users believe expensive or branded gear automatically guarantees performance. The truth is more nuanced.

- Price ≠ Performance: High cost often reflects brand reputation, materials, or design innovations—but isn’t a universal guarantee.

- Fashion vs. Function: Bright colors, sleek cuts, or lightweight designs can appeal aesthetically but compromise durability or insulation.

- Over-specialization: Gear designed for extreme cold may perform poorly in wet environments. Extreme versatility is rare; choose based on your primary use case.

Choosing Gear for Your Adventure

When evaluating gear, ask yourself:

- Environmental Suitability: Does it match the temperature, moisture, and terrain?

- Durability Requirements: Will it survive repetitive stress and rough handling?

- Functional Efficiency: Is it ergonomically designed and practical in the field?

- Emergency Reliability: Will it perform under critical, life-threatening situations?

- Maintainability: Can it be repaired or cleaned easily in remote areas?

A methodical approach reduces the risk of failure. Extreme adventures demand not just high-quality gear but thoughtful preparation.

Case Studies: Gear Success and Failure

Arctic Expeditions

- Success: Lightweight insulated jackets with modular layers, down pants with water-resistant coatings, and high-traction boots allowed explorers to endure -45°C conditions while maintaining mobility.

- Failure: Standard synthetic jackets lost loft when wet, causing rapid heat loss. Boots without proper insulation led to frostbite incidents.

Desert Crossing

- Success: Breathable, UV-protective fabrics, hydration packs, and ventilated headgear kept trekkers safe under 50°C conditions.

- Failure: Non-breathable clothing caused severe heat stress, while poorly ventilated shoes led to blistering and infections.

High-Altitude Climbing

- Success: Carbon-fiber trekking poles, ultralight insulated jackets, and crampons designed for alpine terrain enabled summiting without severe exhaustion.

- Failure: Inadequate layering, weak harnesses, or improperly rated ropes led to injuries and aborted climbs.

These cases underline that extreme-condition gear is as much about thoughtful application as material quality.

The Role of Technology in Modern Extreme Gear

Technology has revolutionized the way extreme-condition gear performs:

- Smart Fabrics: Thermoregulating textiles that adjust insulation dynamically.

- Lightweight Composites: Stronger, lighter materials reduce load and fatigue.

- Integrated Sensors: Some jackets, helmets, and watches monitor temperature, oxygen levels, and heart rate in real time.

- Nanocoatings: Water-repellent, stain-resistant, and antimicrobial treatments enhance durability and hygiene.

The integration of technology doesn’t replace core material science—it enhances it.

Maintenance: Preserving Gear for the Long Haul

Even the most robust gear fails if neglected. Maintenance tips:

- Clean waterproof fabrics with mild detergents to maintain breathability.

- Inspect metal hardware for corrosion or fatigue before and after expeditions.

- Re-waterproof seams and fabrics periodically.

- Store insulated gear loosely to prevent compression.

- Regularly lubricate moving parts on mechanical gear (zippers, pulleys, hinges).

Neglect accelerates wear and can convert “extreme-condition gear” into ordinary, unreliable equipment.

The Psychology of Trusting Your Gear

Confidence in your gear matters psychologically as much as physically. Anxiety over unreliable equipment increases fatigue, distracts from decision-making, and can magnify risk. Investing time in understanding, testing, and maintaining gear fosters a mental edge that is often decisive in extreme environments.

Conclusion: Don’t Gamble with Survival

Extreme conditions are unforgiving. Gear isn’t just an accessory—it’s a lifeline. Materials, engineering, testing, and maintenance all converge to create equipment that performs under stress. Price and branding matter less than understanding purpose, limits, and application. Choose wisely, maintain diligently, and always prioritize functionality over fashion. When the storm hits, the ice cracks, or the desert sun blazes overhead, only gear truly built for extremes will keep you safe and effective.